Robots, Lasers, Glaciers… What?

The Matanuska Glacier, Alaska. Photo credit: Kamal Singh

Well, where to begin?

This is the first in a series of blog posts to cover the Stone Aerospace 2015 VALKYRIE expedition on the Matanuska Glacier in Alaska. We’ll be testing a laser-powered cryobot that will penetrate into the glacier, so that one day we may explore the oceans of Europa, for science.

Whoa there! What’s that you say? Alright, backing up. What even is a cryobot, where is Europa, and why would we want to melt into this beautiful glacier anyway?

A cryobot is a robot that can move through solid water-ice using heat to melt the ice and gravity to sink downwards. You can see a (somewhat old) summary of our cryobot, named VALKYRIE, here. As you can imagine, cryobots are not a very common type of robot, but scientists sometimes tinker with them to try to study glaciers, ice sheets, or bodies of water trapped below the ice (sub-glacial lakes or rivers), because they are more sterile, mechanically simpler, and have less breakage problems than drills. They are also sometimes called Philberth probes, and actually have a fascinating history dating back to the late 1960’s and a pair of German brother priests/physicists named Bernhard and Karl Philberth, who had the crazy idea to use them to sequester nuclear waste beneath the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets during the height of the Cold War (to read more, see this Wired article).

A cryobot is a robot that can move through solid water-ice using heat to melt the ice and gravity to sink downwards. You can see a (somewhat old) summary of our cryobot, named VALKYRIE, here. As you can imagine, cryobots are not a very common type of robot, but scientists sometimes tinker with them to try to study glaciers, ice sheets, or bodies of water trapped below the ice (sub-glacial lakes or rivers), because they are more sterile, mechanically simpler, and have less breakage problems than drills. They are also sometimes called Philberth probes, and actually have a fascinating history dating back to the late 1960’s and a pair of German brother priests/physicists named Bernhard and Karl Philberth, who had the crazy idea to use them to sequester nuclear waste beneath the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets during the height of the Cold War (to read more, see this Wired article).

Were it not for an enigmatic moon of Jupiter, cryobots would probably forever remain a footnote in history. But now it’s time to introduce you to Europa.

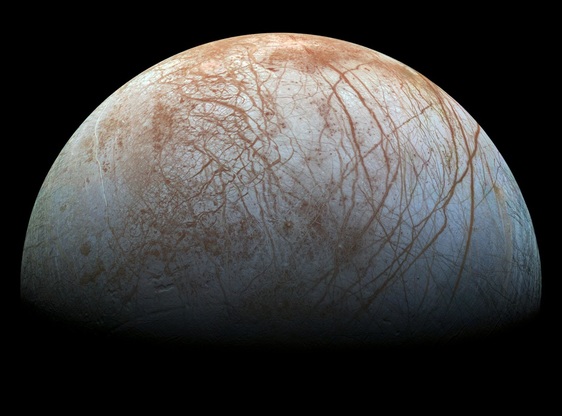

Europa is the sixth moon of Jupiter and one of the most promising places in the Solar System to look for extraterrestrial life. Below the thick ice crust lies a salty water ocean. Photo credit: NASA/JPL

Europa is the sixth moon of Jupiter and one of the most promising places in the Solar System to look for extraterrestrial life. Why is it so promising? The answer, in short: liquid water. When searching beyond our planet for life, NASA’s unofficial mantra long been “follow the water”. This is because, basically without exception, wherever we find liquid water on Earth, we find life*. The conditions can be hellacious – above boiling, below freezing, extreme pressure, more acidic than a car battery – yet somehow, so long as liquid water is present, life manages to make a home.

Europa has liquid water, and a lot of it. Underneath its icy crust, scientists believe there is a salty liquid water ocean with 3 times the volume of Earth’s ocean. This water is kept liquid by tidal heating between Jupiter and Europa. Jupiter is massive, so it has a huge amount of gravity, and Europa has a very elliptical orbit around Jupiter. As the moon swings closer and further away from its planet, the gravitational forces are strong enough to stress and strain the moon itself, and the friction of the repeated tidal flexing heats up the interior, and melts the lower layers of ice. All this flexing of Europa’s mantle means there are likely hydrothermal vents at the bottom of Europa’s ocean, which is where many scientists believe abiogenesis (the origin of life) first occurred on Earth. Furthermore, scientists believe Europa has an active surface-ocean exchange of both oxidants and simple organic molecules created when charged particles are accelerated in Jupiter’s magnetosphere, then slam into Europa’s surface. These molecules could provide a Europan ecosystem with both the building blocks and an energy source for life.

July 2014 cover of National Geographic Magazine. Photo Credit: NGM

So, we have all the necessary ingredients – liquid water, energy sources, the building blocks for life, and a habitable environment. The living conditions in Europa’s ocean may be no harsher than the conditions under Antarctica’s ice shelves – and we know that ecosystems can thrive there. Scientists are really, really excited about the possibility of exploring Europa for life, but so far we have been limited to Mars because it is technologically much easier to explore (because you don’t have to penetrate the ice crust). But recently Europa has been picking up steam. The moon was prominently featured on the cover article of National Geographic’s July 2014 issue, Life Beyond Earth, and for the first time this year, NASA’s budget includes money to begin transforming long requested mission concepts into a real mission, Europa Clipper.

Europa Clipper won’t land, instead it will perform dozens of up close fly-bys of Europa with instruments to characterize the ocean, ice surface, and scout potential places to land. It’s an extremely exciting first step, it will teach us a ton about Europa, and it paves the way for an eventual lander mission which could pierce through the icy crust to get at the juicy stuff underneath.

So that brings us to the final question – what on Earth are we doing running around on this glacier anyway? The answer is: testing an early stage prototype robot funded by by NASA, whose descendant may one day be able to investigate Europa’s ocean**. In the meantime, we’ll be doing some wicked cool glaciology here on Earth, and trying out some brand new ways to get in situ scientific data from our planet’s rapidly retreating glaciers and ice sheets, which could have important implications for climate science.

Stay tuned for more.

*This is not quite true, you also need a source of free energy, and a suite of “biogenic elements” (e.g. carbon). On Europa, the biogenic elements could be provided by organic molecules created by ice surface interactions with ions accelerated by Jupiter’s magnetosphere, subsequently recycled into the ocean, and energy could be provided through oxidation of these and other molecules, or other chemotrophic pathways similar to those seen in hydrothermal vent communities on Earth.

**Actually there’s a number of icy moons in our solar system that harbor sub-surface oceans or lakes, and could be good targets for cryobot probes. Some recent examples that have been in the news are Enceladus, which harbors active water-ice geysers, and Ganymede whose ocean was recently discovered by watching auroras (how cool is that?!).

Reporting by Evan Clark