The Final Mission

Today was a bittersweet day, as it was ARTEMIS’ final mission of the season. The sea ice conditions dictate that we must be completely cleared off the ice by Friday morning. After our previous long sea ice mission, we only had about 4.4 km of fiber remaining – not enough for another long mission. So we decided the best return on our remaining resources would be to conduct one last mission on the safety line investigating the sea ice / ice shelf transition in detail, which is well within our 1 km on-safety-line operational radius.

For those who need a refresher, an ice shelf is glacial ice that formed on land and flowed off the continent to float on the ocean. The portion that is still on land is called the ice sheet, and the portion floating on the ocean is the ice shelf. Ice shelves are much thicker than sea ice, and their buoyancy helps support the weight of the ice sheets (glaciers) on land. This is why people are worried about them melting – if an ice shelf collapses, all the glaciers it holds up are free to slide into the ocean, which could raise global sea levels significantly in a short amount of time (meters, in the case of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet). It is a common misconception that melting icebergs raise sea level, but this isn’t true. Try putting a piece of ice in a glass of water and letting it melt – it doesn’t change the water level! What scientists are worried about is new ice entering the ocean because the ice shelves are no longer holding up the ice sheets.

Sea ice is ice that formed from the ocean itself, and is much thinner than an ice shelf. Sea ice more or less melts and reforms every year with the seasons (there are some places with multi-year sea ice that does not melt completely). Our camp is on sea ice so that we can more easily drill through it to give ARTEMIS access to the ocean beneath, but this also means our season must end once it is no longer safe to be out and about on the melting sea ice. We really don’t want to fall in!

We conducted several zig-zag transects across the ice shelf transition with water samples along the way. Some of these transects were as close as possible to the ice ceiling to gather fine-grained sonar and imaging data, and some were further away to gather “patch tests” to help us determine the precise physical misalignment between the robot’s navigational center and our acoustic mapping instruments, which will help us improve the quality of our maps in post-processing. I really enjoyed this mission because I got to fly ARTEMIS super close to the ice with challenging topography, Mark was stoked about the patch test data, which he has been thinking about for years, and Britney was excited about all the ice interaction science. We were all fascinated by the fact that this and every other time we have passed the transition, we have seen a huge abundance of wildlife (fish, shrimp, jellies) hanging out here compared to other places. Why do they like it here? We don’t really know. But understanding why might help explain some dynamics of ecosystems in ice-covered environments, which in turn could inform our search for life in Europa’s ocean.

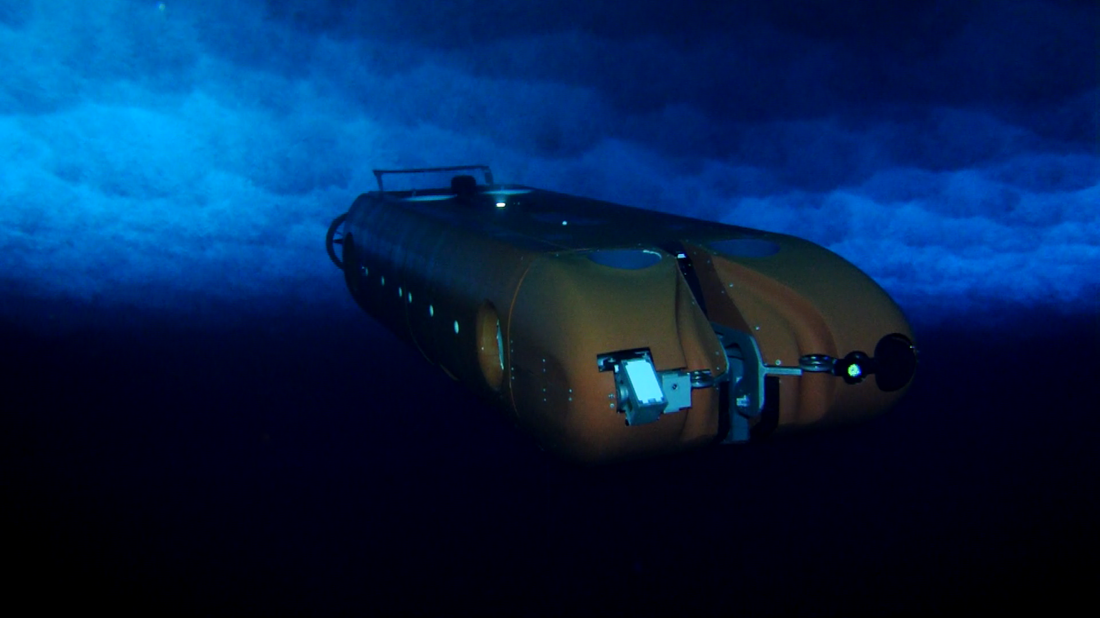

A last view of ARTEMIS under the sea ice near the borehole during the final mission. (Photo: Bill Stone).

The next few days will be tearing down what remains of camp, hauling it back to town, and starting the long packing process to ship it off the continent. Brian, Luke, and I leave on Thursday, and most of the rest of the crew leaves on the 17th. We’ll miss this place, the people, the adventure, and the beautiful things we’ve had the opportunity to witness through ARTEMIS’ eyes.

Reporting by Evan Clark