Matanuksa Glacier, Alaska

June 17th – 26th, 2015

Let the science begin

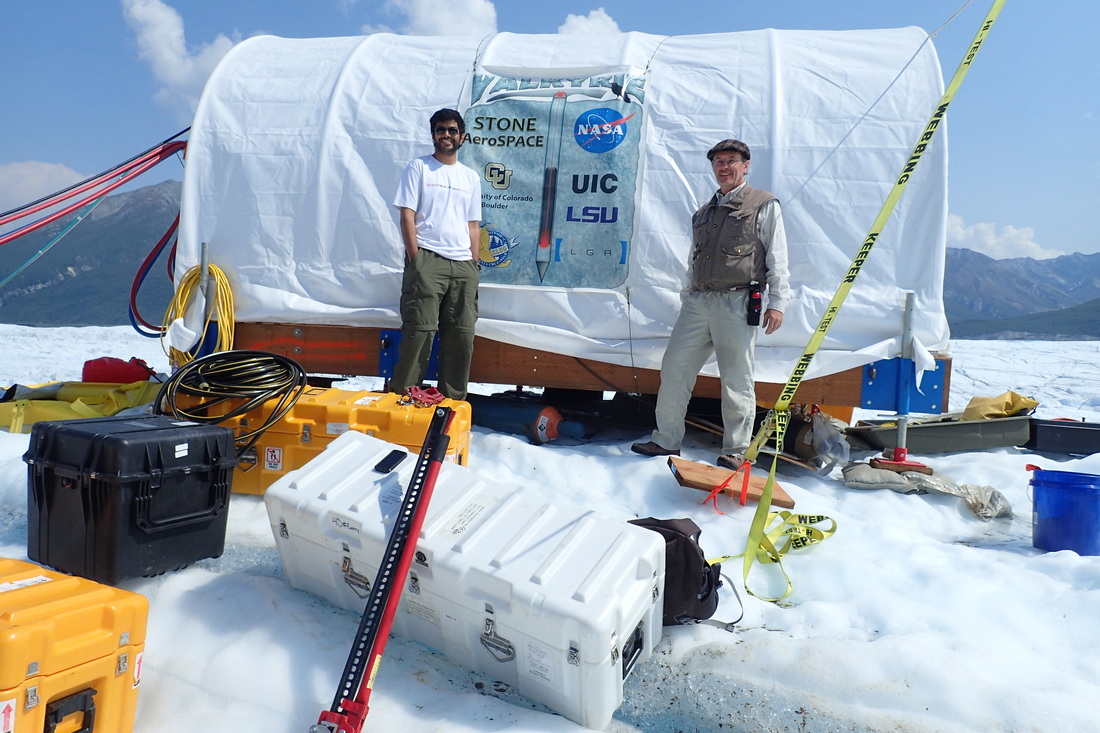

Time flies here, and I’m already behind on blog posts! Things have been a whirlwind of activity. On June 16th, the day after I arrived on the glacier, the first batch of scientists arrived in Anchorage, as well as the chief engineer for VALKYRIE, Bart. The scientists are: Al, a professor at UC Boulder, and his graduate student Omkar, and Sarah and Vicky, who are PhD students at UCSC studying Glaciology and Paleoclimatology respectively. Al and Omkar are testing an ice-penetrating synthetic aperature radar that will be mounted on future versions of VALKYRIE and will allow the robot to steer away from obstacles or towards targets of scientific interest in the ice. Sarah and Vicky are using ground penetrating radar to measure the glacier’s depth, phase sensitive radar to measure the glacier’s melt-rate, time lapse photography from a camera on a moraine ridge to measure its flow speed, and embedding sensor strings into the ice to measure shear and temperature.

Vicky and Sarah were able to make it up to base camp on the evening of the 16th, but Bart, Al, Omkar and Vickie S. were delayed until the next morning by down-slope crosswinds which made bush plane landing unsafe, so they slept at the tongue of the glacier.

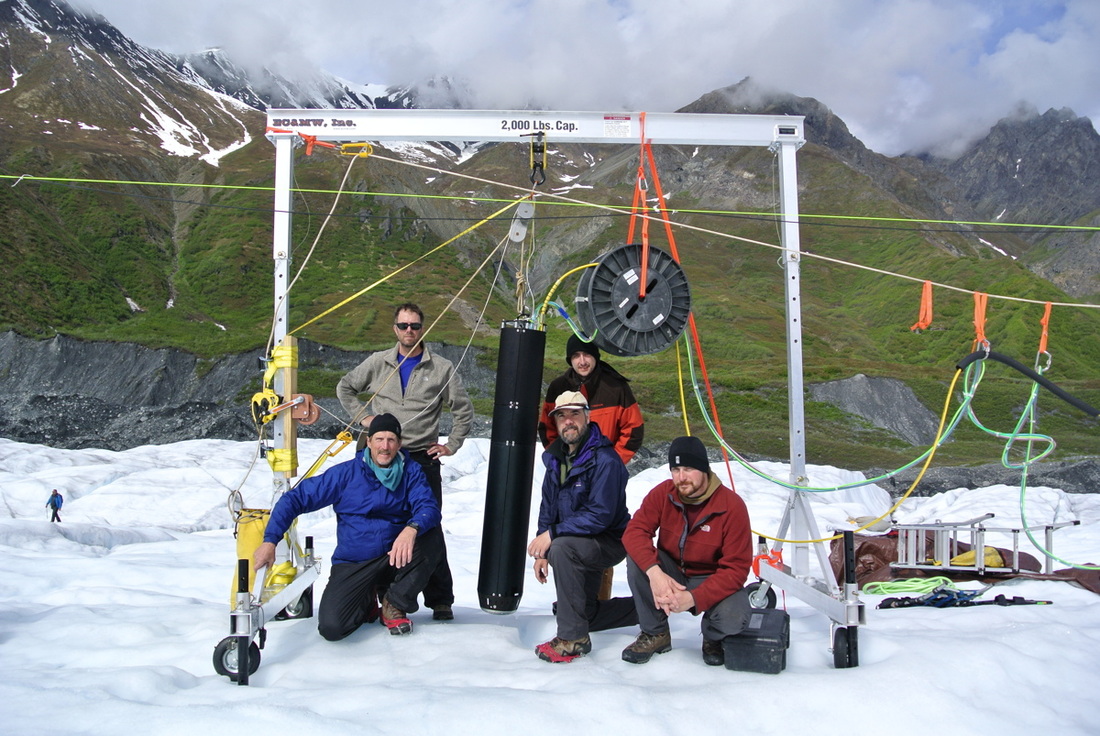

Al prepares the gantry and melt hole for a synthetic aperture radar run

Sarah and Vicky’s timelapse camera watches over the glacier

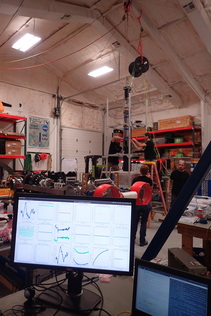

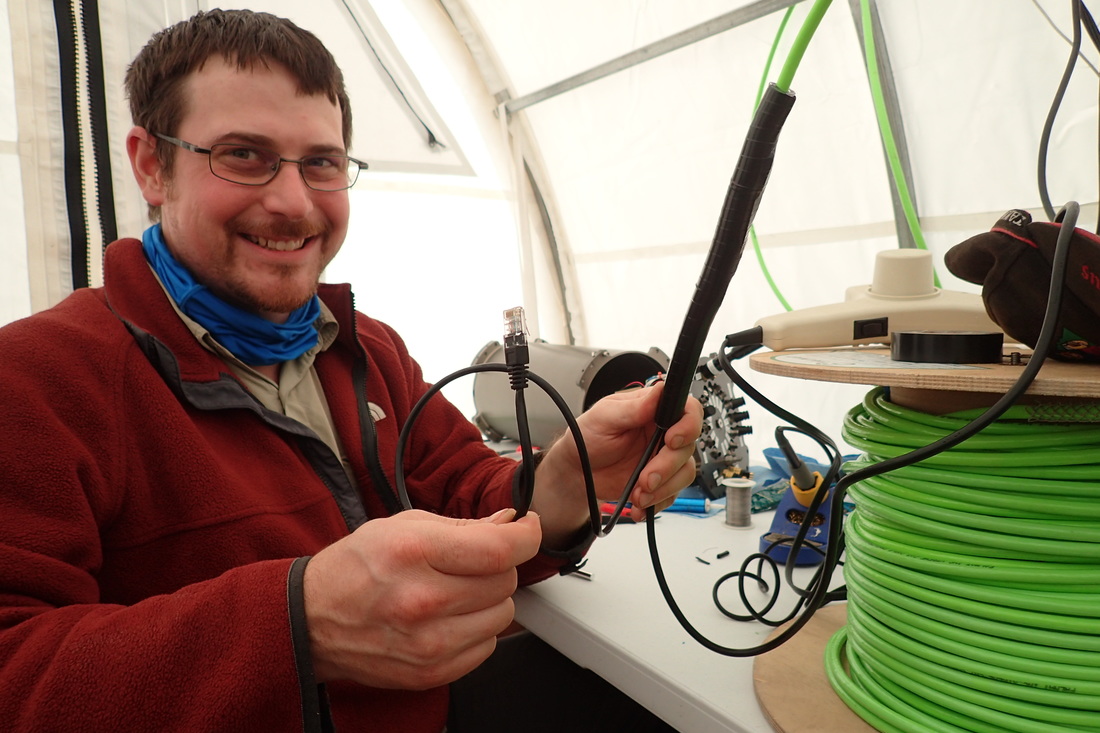

Once everyone arrived, the scientists began their experiments, and we Stone Aerospace engineers kept busy setting up mission control, re-assembling the robot (it had to be disassembled to be transported – it’s too long!), unpacking, and figuring out what to do about all the things that were inevitably forgotten or broken between lab in Austin and here. One of the most important things we managed to forget was a pig-tail power and data connector that connects the robot’s tether to mission control, which we can’t run without. John and I spent a full day searching through all the boxes, searching them again, and then finally cutting and splicing a spare cable into what we needed after determining that the connector was left in Austin. I am learning once again how much harder it is to do anything in the field – even something as simple as connecting a cable can take a whole day by the time you’re done. There’s just so much friction, and things you can usually take for granted are either unreliable or absent. In computer science there’s a term for this that amuses me: “Yak Shaving” – when you have to spend a huge amount of time setting up the system, just to do something easy. The pile of yak hair is growing large out here…

John splices the power and comms pigtail

Ready to roll!

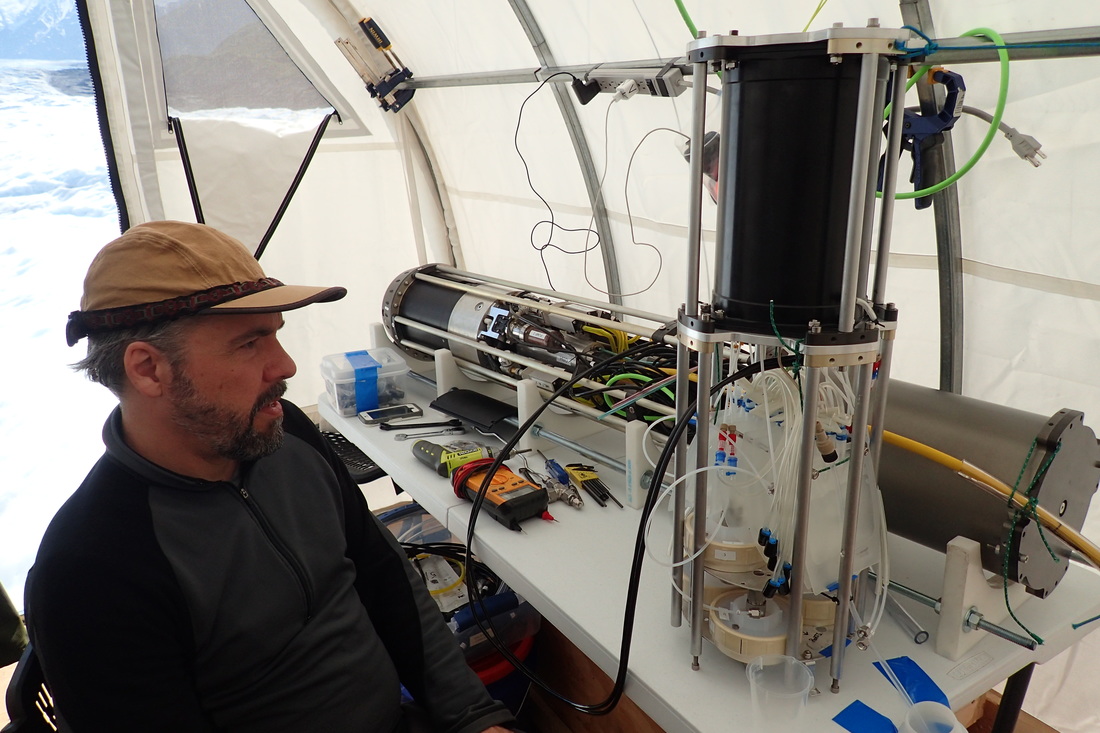

Bart assembles the water sampling system that will be bolted onto the back of the robot as part of the new science package. “Last year’s” robot is visible in the background

Because we weren’t yet ready to melt holes with VALKYRIE, and Al and Omkar’s radar measurements are physical, not biological (and thus they aren’t worried about biological melthole contamination), they melted holes with the Hotsy. The Hotsy is basically a diesel water heater connected to a garden hose. Poor Omkar didn’t have nearly as good of a mission control tent as us, and was camped out under a tarp with a camp chair and his computer, but he was a trooper. Every time they melted a few inches deeper, he yelled out “Haul!” and Al lowered the radar to the bottom of the hole with a winch. As to not distort their radar image, it’s important for them to keep the radar moving at a constant velocity through the ice. It’s very tedious work, and they were out in the sun and cold all day every day doing this. But it should yield awesome results imaging the glacier below. The things we do for science…

Meanwhile, Sarah and Vicky hiked around the glacier taking depth, meltrate, and flow measurements using their various radars and cameras. In the longterm, they hope to understand the physical characteristics of the glacier.

I’ve had my head buried in the ground with this robot for so long, it’s cool to see all the other aspects of the VALKYRIE Project science that I haven’t necessarily been aware of.

Al and Omkar lower their custom ice-penetrating synthetic aperture radar into a melt hole.

The SAR down the melthole. Future versions will allow VALKYRIE to “see” ahead of itself in the ice

Team UC Boulder, happy at the end of their deployment

Al and Omkar finished up their experiments, and were pretty pleased with their preliminary results. Because camp can only support a limited number of people, and it’s cheaper to batch bush plane flights together (so both up-glacier and down-glacier flights are utilized), when one group of scientists leaves, the next group typically comes in at the same time. Al and Omkar left on the 23rd and were replaced by Nathan.

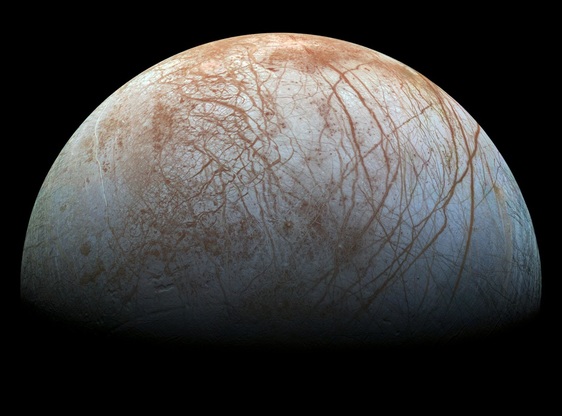

Nathan is a key player in this year’s expedition. He designed a “flow cytometer” instrument that will bolt on the end of last year’s robot and is a primary component of this year’s new science package. “Flow cytometer” is what we call it for lack of a better name, but it not really a traditional cytometer, which counts only a single cell flowing through at a time. This has a much greater diameter viewing window, and it measures the fluorescence spectrum of all the meltwater passing through it at once. Nathan has characterized a series of spectral “fingerprints” for various components of interest that could be in the water (e.g. general proteins, chlorophyll, various minerals), and our software does real-time chemometric fitting of this data to determine how much of each component is in the water. A large part of our mission this year will be collecting data to characterize this instrument. If things go well, we’ll use the real-time data to autonomously trigger water samples based on interesting content in the water, which can then be brought back to lab for further analysis. This will be the first autonomous sample collection by a cryobot, and a big step towards an eventual Europa mission, where no scientists can be around to direct the robot!

Storm clouds settle in over a river channel cut through the ice

The glacier continues to astound me. It has moods, just like a human, and lives in constant flux. I bring all my warm clothes to the glacier every day, even if it is warm and sunny in the morning, because it could pour freezing rain within an hour. Weather predictions are useless; all there is here is now. Sometimes a curtain of rain will ride howling winds ominously down-valley towards us, obscuring the entire pass in darkness, only to change its mind a mile away and retreat back over the peaks from which it came, leaving us blinking in the sunlight like nothing ever happened. Sometimes it will stay the course, and during those times I’m glad to be warm and dry in mission control.

Also like a human, the glacier is full on contradictions. The most beautiful to me is the contrast of jagged and organic, linear and smooth. The glacier is shot through with cracks and linear features, many of them filled with water and refrozen into pure blue ice, then overturned in layers to create planes slicing at every angle. But it is also carved by water in lazy snake-like patterns, large looping oxbows, and smooth scalloped waterfalls. Occasionally, one of these curving rivulets will find a refrozen crack and follow it on to the next and the next; suddenly the path of the water will shift from smooth sinuous S’s to zig-zagging Z’s.

The glacier changes rapidly. Here a rivulet of water traces a lazy oxbow.

The next day the water has broken through the wall and cuts a new path.

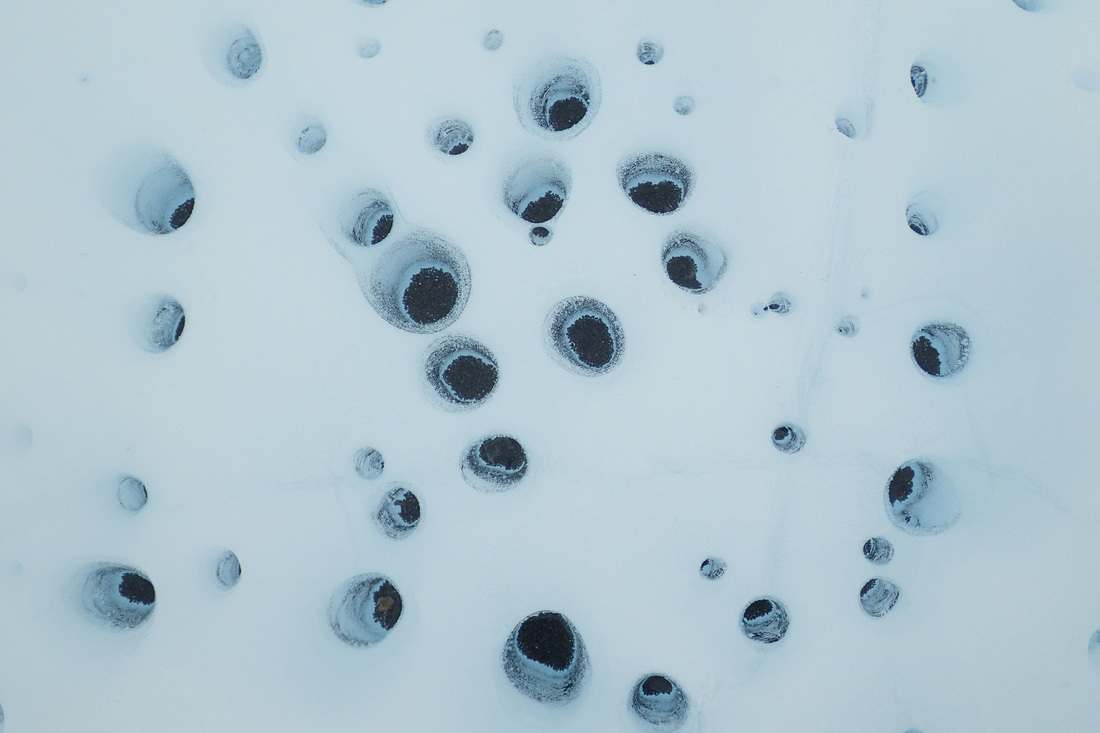

The surface of the ice is also in rapid flux. Endlessly bombarded by sun, it is continuously ablated away. Any darker sediment on the surface heats up, and melts a hole down into the ice (much like VALKYRIE), until these dark particles melt deep enough that the sun cannot reach them because the hole is too deep, so they stop heating. Then the surface ablates away, making the hole shallower again, and the process repeats, in inchworm fashion. These holes are called cryokonites, and each is a mini self-contained microbial ecosystem. Every square inch of the ice is covered with them, and on particularly sunny days, it looks like someone has blasted the entire glacier with a sandblaster from above.

When dark sediments on the ice surface are heated by the sun, they melt downwards, much like VALKYRIE. These holes are called cryokonites, and each is its own miniature microbial ecosystem.

The cyrokonites are not the only sign of the constant ablation. The glacier is also ablating out from underneath us and our science structures. If we do nothing, our structures will soon slide away as the ice is melted out from underneath them on the uphill side. Within a few days, flat ice becomes an increasingly precarious pedestal. Periodically, Josh and Vickie must go around to all of the structures, lift them up on farm jacks, chip the ice pedestals flat, and adjust the 6 legs of the structure (also on jacks) to some semblance of level again. If you’re inside mission control when this happens, it feels like being on a ship.

The ice continually melts away beneath our structures. Every few days, Josh and Vickie chip flat any “pedestals” developing under Mission Control’s legs, and adjust the jacks to re-level the floor.

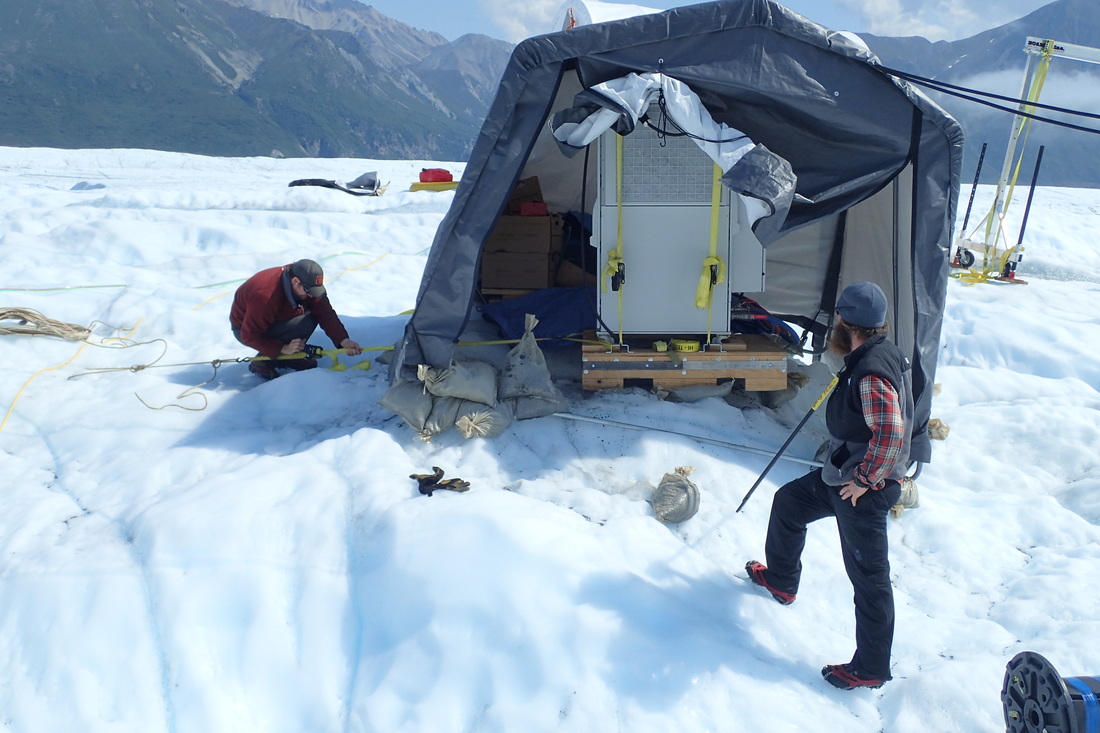

The chiller is not on an adjustable platform, so it is in more danger of sliding away. John periodically uses a V-anchor in the ice and a webbing winch to pull it up to flat ground.

We’ve been working very hard and will have the robot fully assembled and all the logistics in place soon. Once that happens, we’ll be ready to fire up the laser to start making some VALKYRIE test holes. Stay tuned…

A quiet moment at Mission Control.

Walking home in perpetual twilight after a long day of work.

Reporting by Evan Clark

A cryobot is a robot that can move through solid water-ice using heat to melt the ice and gravity to sink downwards. You can see a (somewhat old) summary of our cryobot, named VALKYRIE,

A cryobot is a robot that can move through solid water-ice using heat to melt the ice and gravity to sink downwards. You can see a (somewhat old) summary of our cryobot, named VALKYRIE,