West Lake Bonney, Taylor Valley, Antarctica

Reporting from Blood Falls Basecamp

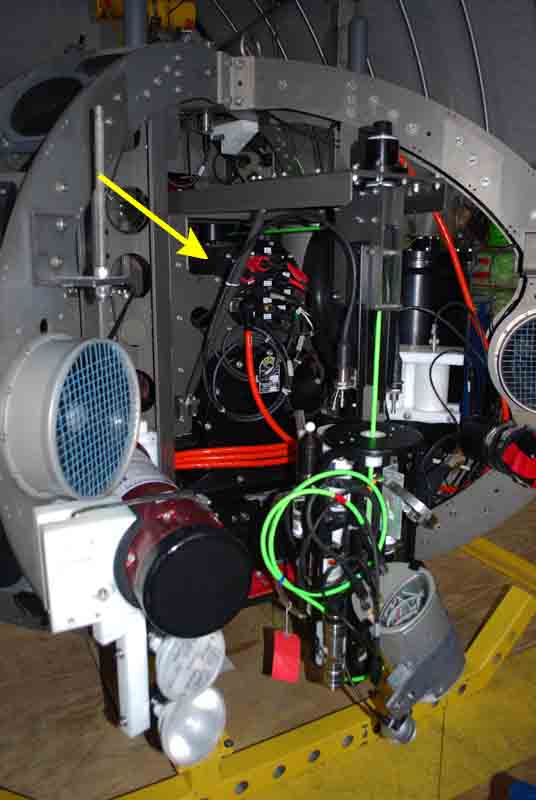

Our successful sonde mission yesterday had us convinced that we were over the hump and would just be running uneventful missions from here on out. Chris, Bart and Kristof took some time in the morning to change the lens and adjust the focus on the sonde camera, so that our images of the lake floor would be crisp.

Bart and Chris work on focusing the camera on the sonde.

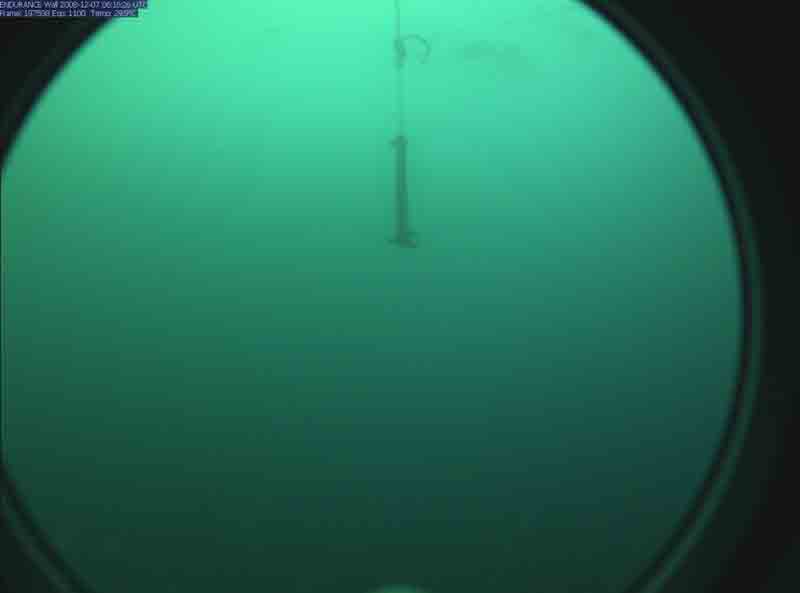

Once they were done, we sent the bot out on its mission for today, nine sonde drops. At the first grid point, we began to lower the sonde but less than halfway down the drop the data coming from the altimeter turned to garbage. The altimeter sits near the bottom of the sonde and tells us how far the sonde is from the bottom as it is slowly lowered. For environmental and hardware reasons, we want to avoid letting the sonde bump into the lake bottom. Normally the sonde is lowered until the altimeter indicates that it is 1 meter above the bottom. Without good data from the altimeter it is difficult to know when to stop the sonde drop and there is really no way to continue the science mission from that point, so we aborted the mission and called the bot home. Strangely, the altimeter resumed normal operation somewhere on the trip home.

Back in the bot house we started to work on the problem. We pulled the bot out of the water and, thinking that the garbage data might have been caused by a poor communications connection somewhere between the altimeter and mission control, we started to check the altimeter’s connections in the electronics housing in the sonde. Everything seemed fine, and anyhow, the altimeter now seemed to be working. We spent some time dropping the sonde in and out of the water and correlating the altimeter readings to the encoder on the spooler. Coupled with a depth-under-keel measurement from the sonar units, this gives us an additional way to know how far the sonde has been spooled out and how much distance is left as it approaches the bottom. Assuming that we don’t see anymore problems from the altimeter, tomorrow we’ll be back to running missions.

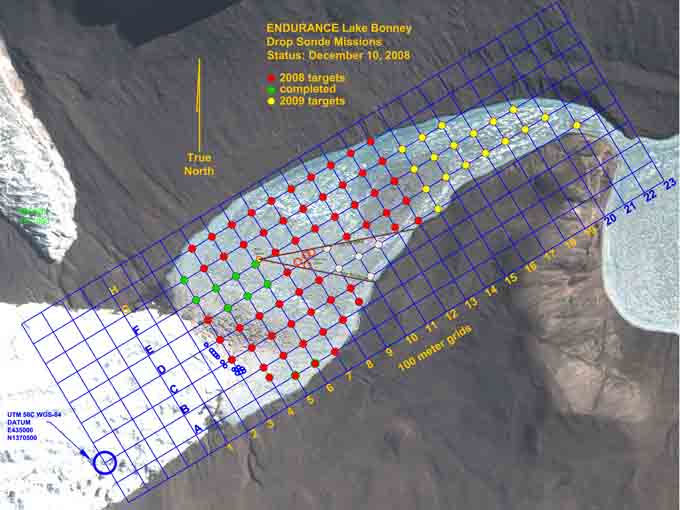

A Quickbird satellite image taken recently shows our camp and Bot House on West Lobe Lake Bonney.

Reporting by Vickie Siegel