West Lake Bonney, Taylor Valley, Antarctica

Reporting from Blood Falls Basecamp

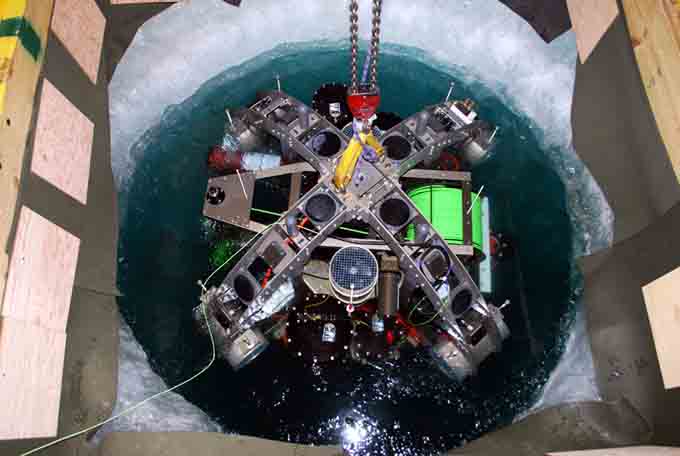

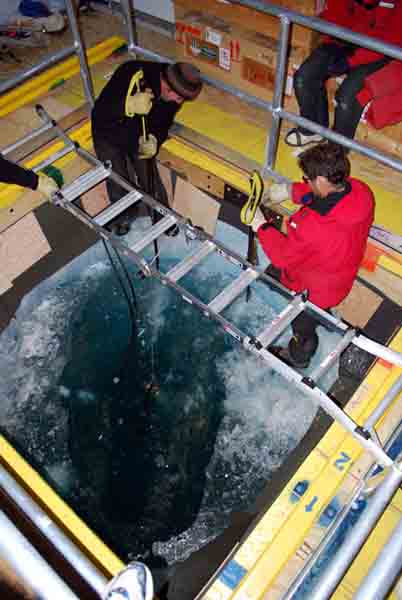

Today’s testing schedule included doing some ground truthing of the navigation programs and to test our recovery beacon. Happily, it was easy to do both at the same time, since we could use the recovery beacon to locate the bot and verify if it actually navigated to the points it was programmed to go to. We sent the bot down under the ice and gave it some coordinates to drive to about 10 meters away from the Bot House. Bill and Vickie, meanwhile, suited up and went outside with the loop antennas.

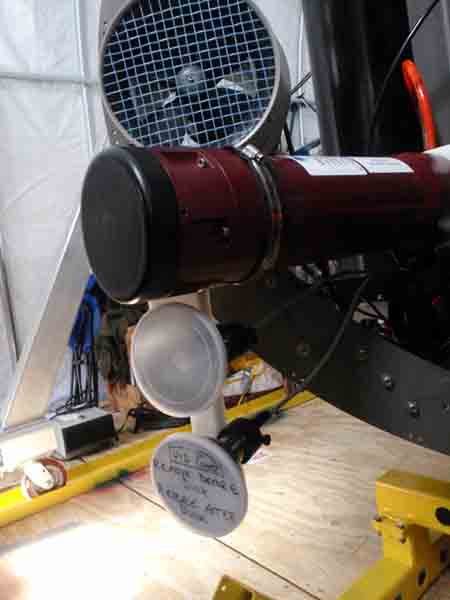

Our recovery beacon is a meter-long cylinder that hangs inside the bot frame and produces a magnetic field. The field can be sensed above the ice by a loop antenna, essentially a coil of wire about half a meter in diameter. The loop antenna plugs into a receiver box and the receiver box has a set of headphones. The operator wears the headphones and can hear the signal. When the signal goes null, or makes no noise, then the loop is pointed directly at the robot. When there is a loud tone then the loop is pointed away from the bot. With two people using loop antennas, it is a simple matter to zero in on the beacon.

When mission control radioed that the bot had reached its waypoint and stopped, Vickie and Bill located the bot and marked the spot with an ice screw. A GPS check confirmed that the bot appeared to be navigating correctly. Good news!

Kristof, Shilpa, and Chris track the bot’s progress from mission control.

The next thing Peter wanted to check on was a mystery object stuck in the lake. Several researchers have worked in Lake Bonney over the years and occasionally the equipment from their various experiments—ropes, sediment traps, stakes, etc.—is lost or forgotten in the lake ice. One of our biggest fears is that Endurance will run into one of these objects dangling below the bottom surface of the ice and get the fiber optic snared. When we chose the site for our Bot House, Maciej found some crossed bamboo stakes lying on the ice nearby. It turned out that there was a string tied to them and some sort of object, one of these old experiments, dangling from the string in the water. We navigated to where we calculated the bamboo stakes to be and, approaching carefully, looked at this mystery obstacle through the forward looking camera. We could see some sort of dumbbell-shaped object but couldn’t tell what it was. Maciej then melted the object out of the ice. When Peter returned to the Bot House carrying the retrieved object we all crowded around. It was much smaller than it looked on the screen and no one had any idea what it was, just that it was corroded and crusted with salt that had precipitated onto it from the salty lake. While it remains a mystery, we’re just happy to have this obstacle removed from our path.

Peter displays the mystery experiment pulled out of the lake. The white goop on the body of the thingis salt from the lake. We salvaged the square of Plexiglas for use as a prototyping material later -you never know what you’ll need in the field.

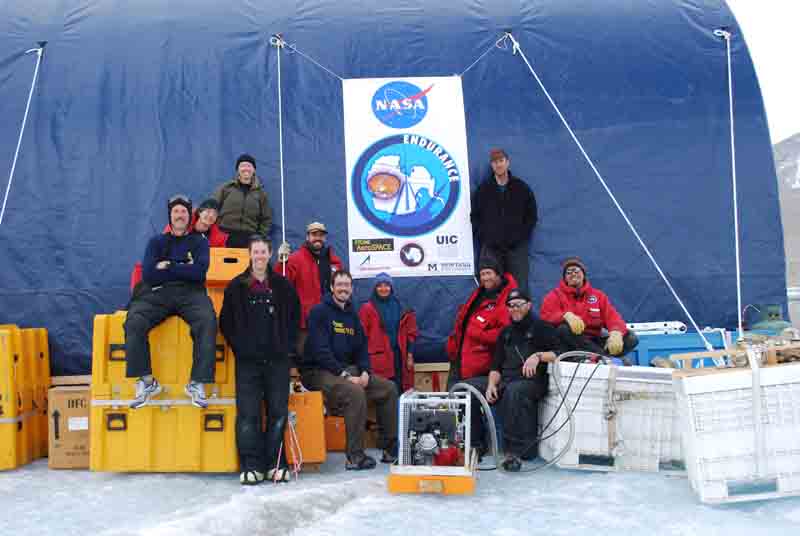

While today went well, the end of the day was still a bit of a bummer. Bob and Annika left on a helo flight this afternoon and after a day or two in MacTown they’ll be heading off to holidays in New Zealand. Thanks for your help guys, we’ll miss you!

One last shot of the team before Bob and Annika leave. From left to right: Bill, Chris, Vickie, Annika, Bart, Kristof, Shilpa, John, Peter (standing in back), Bob, and Maciej.

Reporting by Vickie Siegel