West Lake Bonney, Taylor Valley, Antarctica

Reporting from East Lake Bonney Basecamp

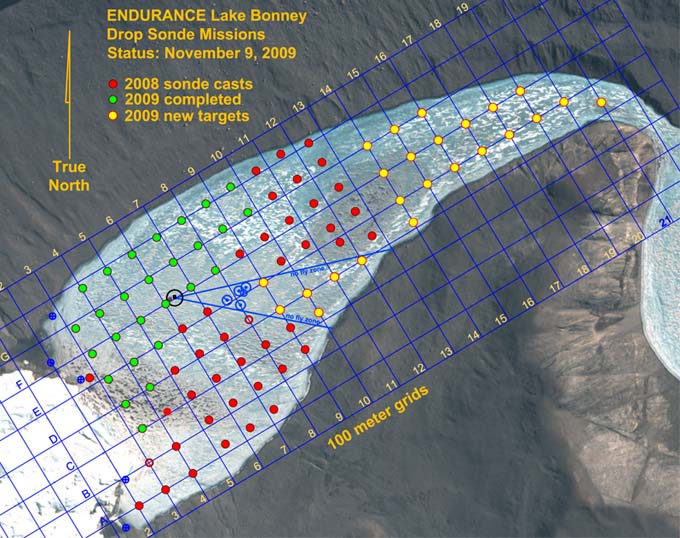

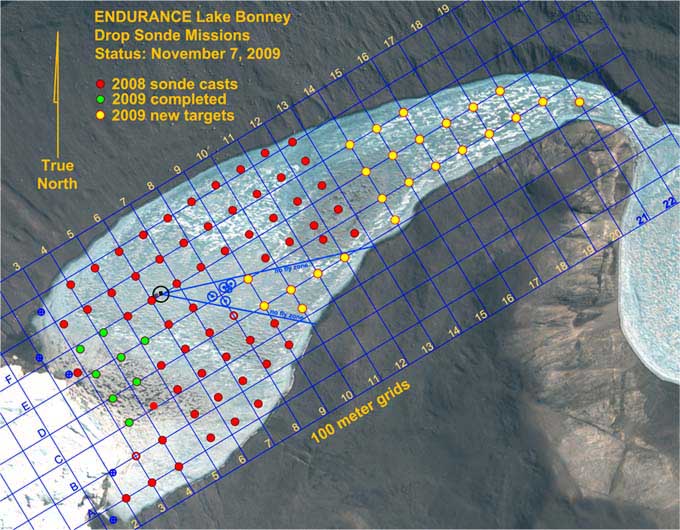

Today was to be the first long range mission, going 300 meters further east than we had reached in 2008. In preparation for this we re-spooled a new 2 kilometer data fiber we had commissioned for 2009. This, plus mission planning and software upgrades keep everyone busy until 2:45pm when the mission got fully underway, targeted at achieving 19 sonde drops. We had sunny weather with a persistent 10 knot wind coming up the valley from McMurdo Sound.

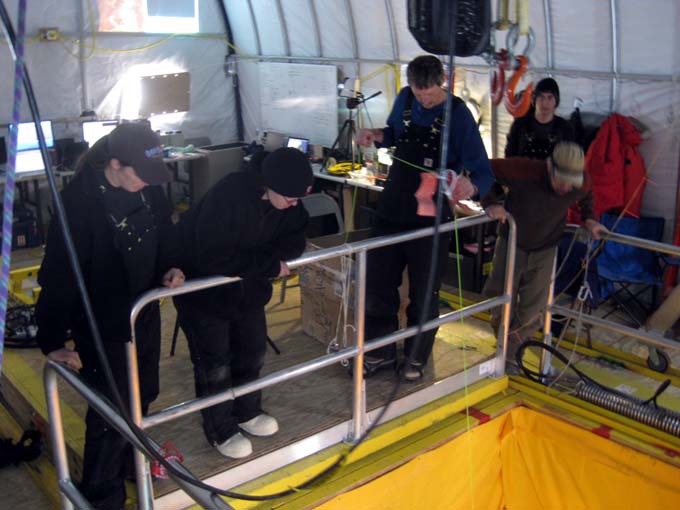

Vickie “flakes out” the 2 kilometer data fiber spool so that it will deploy without hockling (a tendency of coiled ropes, fibers, and cables to form loops).

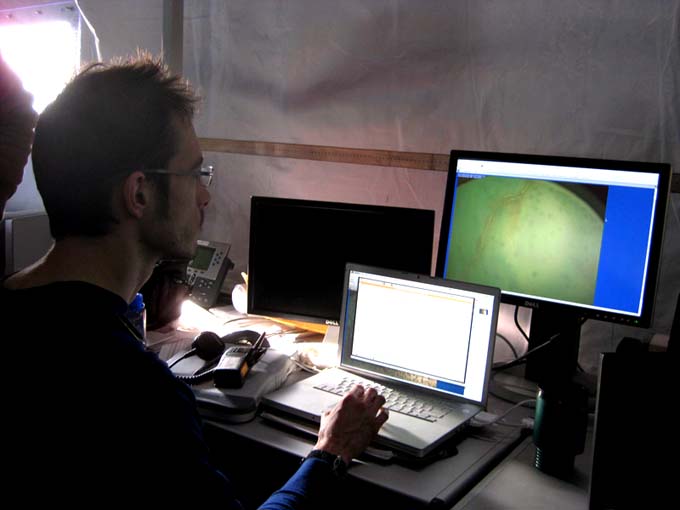

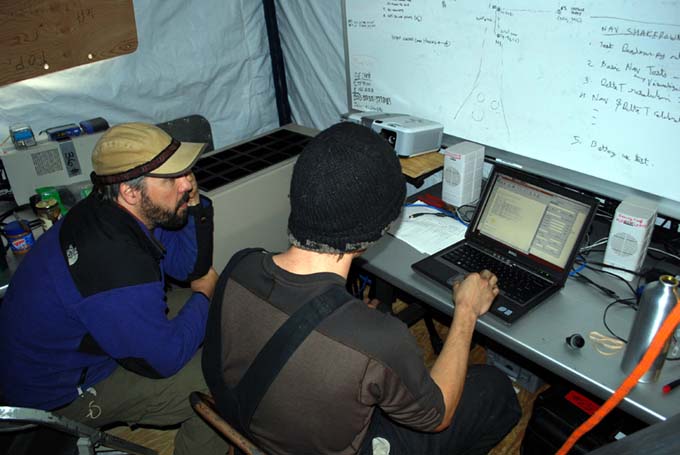

We had already logged the first sonde cast (F10) and were localizing the vehicle at G11 when at 4:45PM mission control called to indicate communications went down on the bot. The team at mission control tried rebooting; changing the short fiber from the main targeting computer; changing the fiber optic to Ethernet conversion boxes, but no go. They then began pulling fiber in to test if communications would come back—due to a kink straightening out—but also no go. So Bart and Kristof began pulling it back using the fiber with a slow, steady 2 kilogram force—enough to gently get it moving under the ice cap. Vickie and Bill tracked it for 50m to assure it was pulling straight back towards the bot house before packing up and returning the remaining 400 meters on foot. The vehicle was in the middle of a sonde caste when the communications had gone dead so it was unclear whether the sonde mission completed and the instrument package homed to the bot.

Bill operates an instrument for measuring the surface albedo at station F10. These data will be used to cross correlate PAR (photosynthetic active radiation) readings from the vehicle sonde sensors with surface illumination.

Vickie grabs a quick bite of lunch while waiting at station G11 for a decision from Mission Control (450 meters away towards the glacier) on the status of the vehicle.

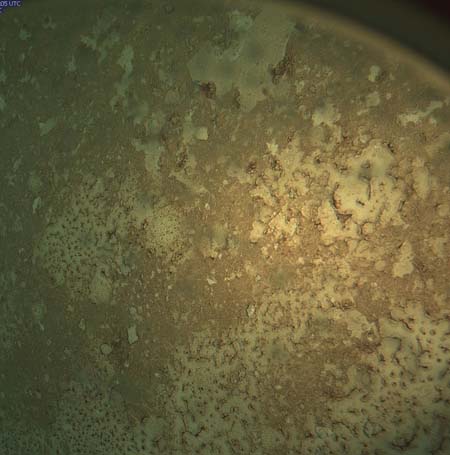

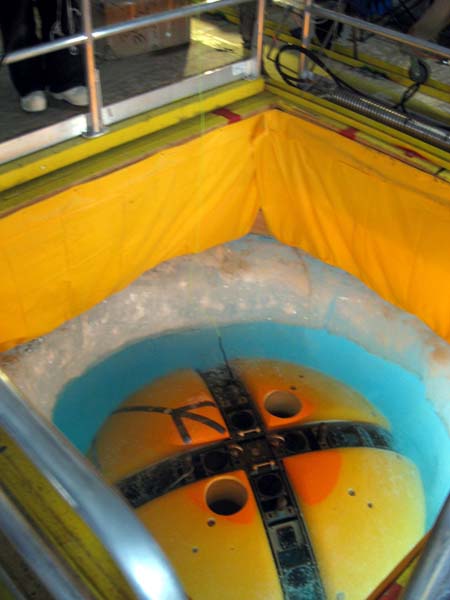

The vehicle successfully returned to the melt hole at 7:44pm, whereupon an extensive investigation began that would last another day. It was floating neutrally in the water, an important sign that there had been no housing leaks. We made a direct fiber optic connection (bypassing the 2 kilometer spool) but still no connection. Similarly, a wireless link that was activated when the bot was out of the water also would not work. We discovered when the bot was hoisted out of the water that the sonde had not reeled back in—indicating a significant communications problem had affected all systems at once. Vickie connected a diagnostic serial communications cable directly into the Profiler housing and Chris was able to verify that the bot had significant reserve power and was responsive to direct local commands—and we thus respooled the sonde—about 26 meters had been paid out at the time of failure. Further investigations through other independent instrumentation data ports showed that the main processor stack data router was down. We were able to talk to the cameras and several other key instruments but it was the main processor stack that issued commands to operate the various parts of the vehicle. The batteries had more than 50% power remaining. An independent test of the 2 kilometer fiber showed that to be operating as expected.

At 9pm we recycled vehicle power and the wireless link came up temporarily then crashed. We then opened up the main processor housing. There were no “smoking guns” that would suggest a shock-induced failure (e.g. a loose connector from impacting the underside of the ice during ice picking). We held a team meeting to discuss and the general consensus was that oxidation on wires from internal power supply to router may be the problem—will investigate tomorrow.

Reporting by Bill Stone