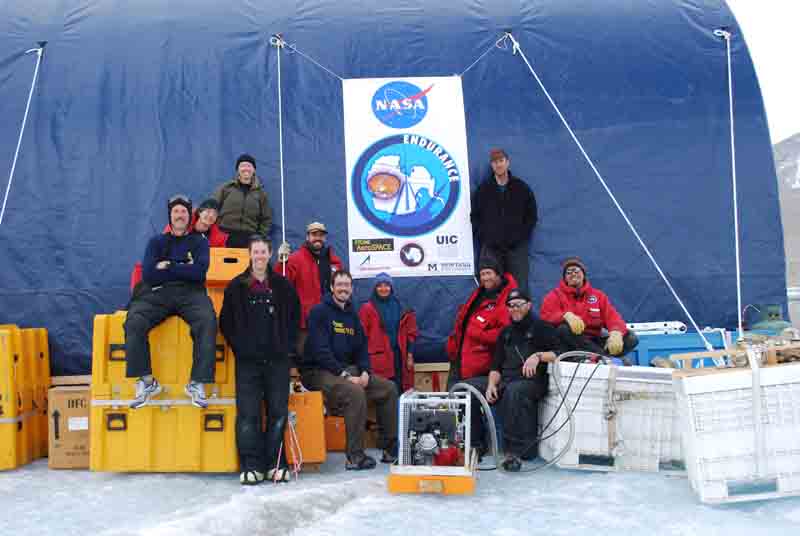

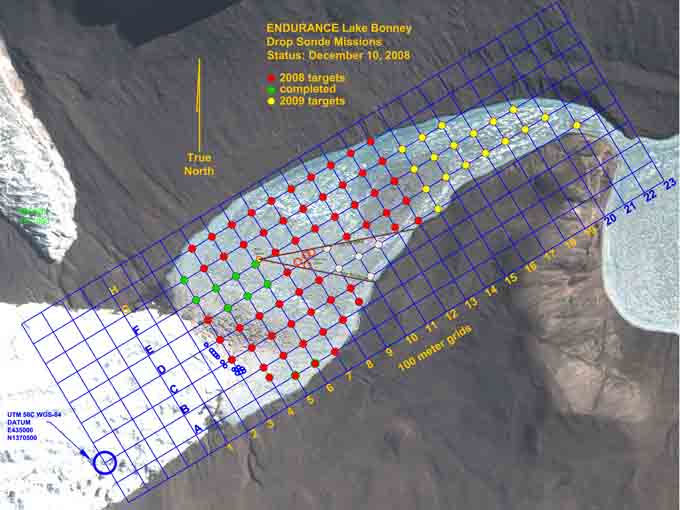

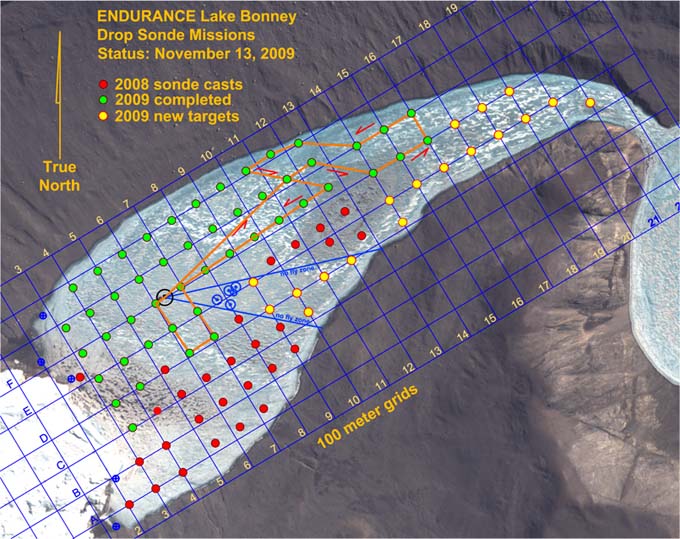

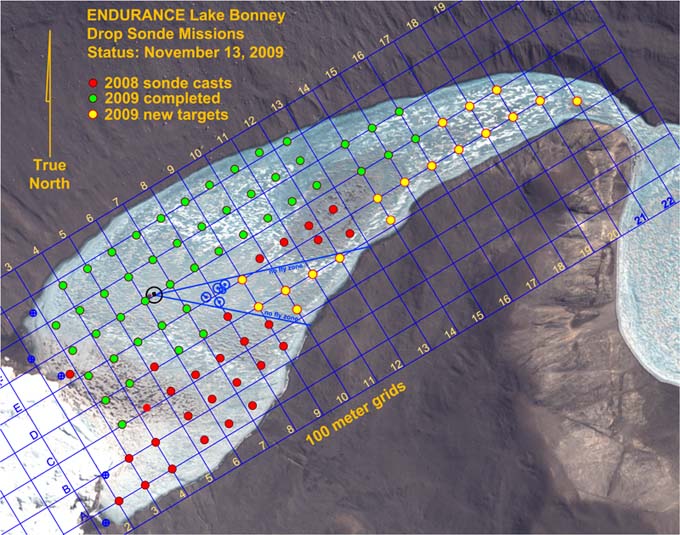

West Lake Bonney, Taylor Valley, Antarctica

Reporting from Blood Falls Basecamp

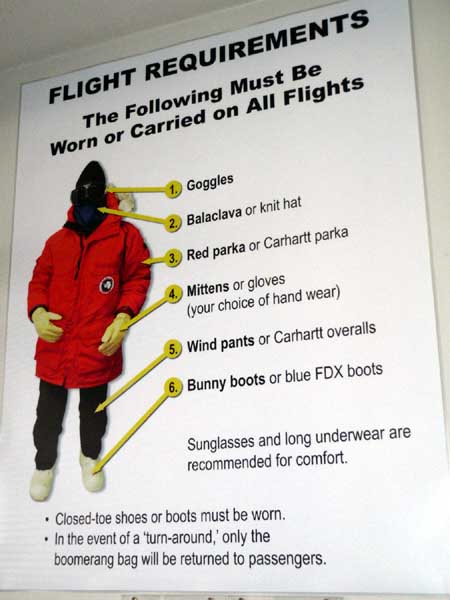

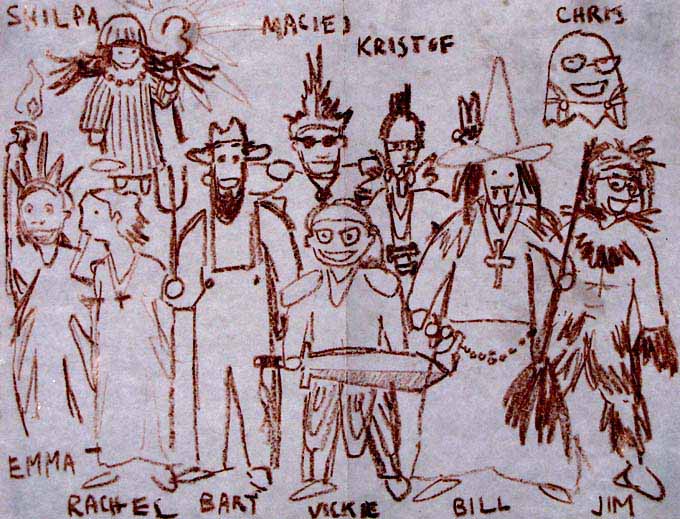

Our first day in the field! This morning we started off by enjoying our last prepared breakfast in the McMurdo Station dining hall and then checked out of our rooms and headed down to the helo pad for our flight to the west lobe of Lake Bonney. The plan was that Peter, Bill, Kristof, Bob, Annika, Maciej and Vickie would head out to the Blood Falls campsite and start to set up the Bot House platform on the lake ice. Chris and Shilpa would join us in the field on Friday. Maciej and Annika left town on the first flight to run some errands at the Lake Bonney camp before the rest of us arrived. After we selected our helmets and weighed ourselves, the helo technicians loaded our duffel bags into the Huey and we all squished into the remaining seats. The rhythmic thud of the rotors accelerated and we were carried over the white expanse of the Ross Ice Shelf and into the stark grey granite walls of the Taylor Valley.

After the scenic 40 minute flight we arrived at the Blood Falls Camp site, named for the dark orange streaks in the iron stained glacier nearby. McMurdo carpenters had already set up two small weather haven tents for us and a couple helo sling loads of our camp gear had already been delivered that morning. We took a couple of hours to set up camp. We decided to use the smaller weather haven as a kitchen and the larger red haven as a dining room. We set up our tables and chairs, moved food into the kitchen and set up our personal tents.

A sling load and our duffel bags on the shore of Lake Bonney, at Blood Falls Camp.

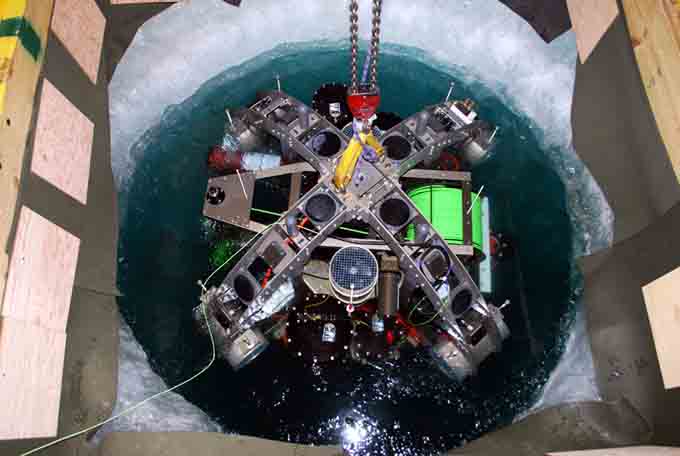

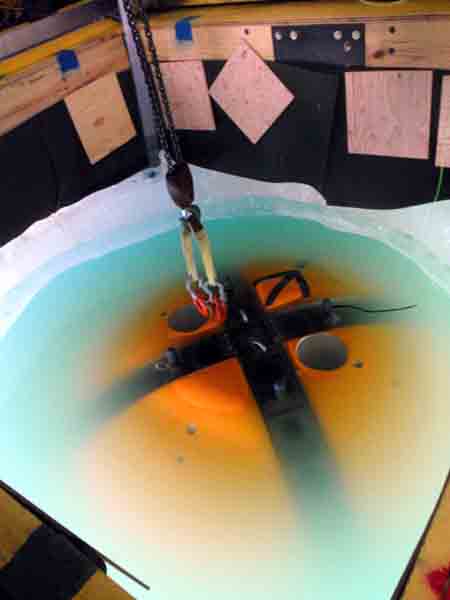

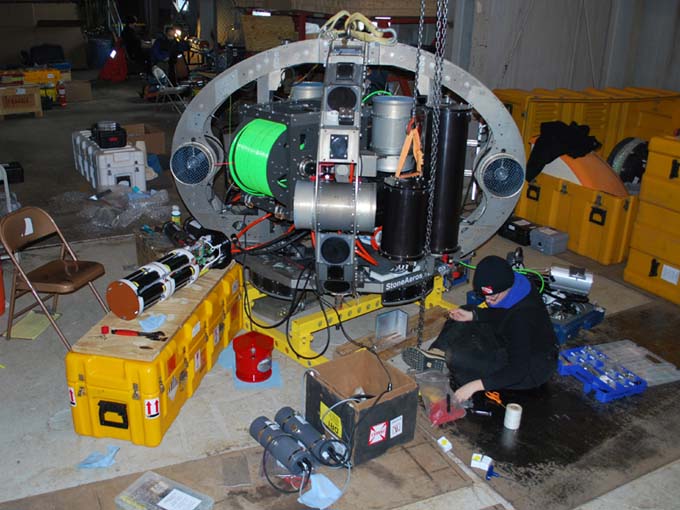

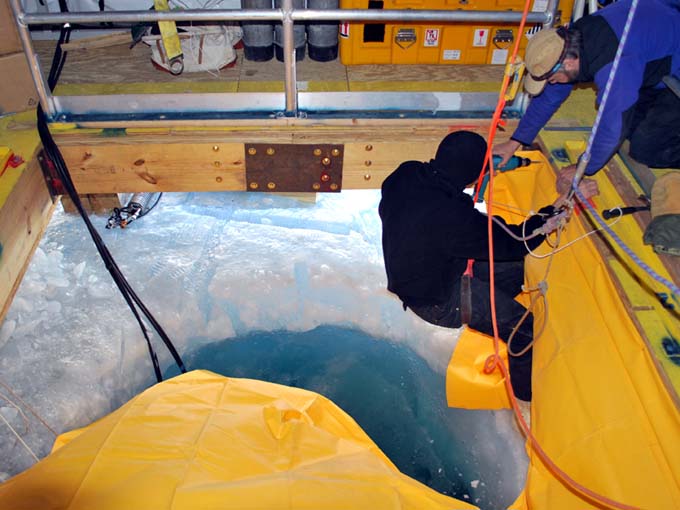

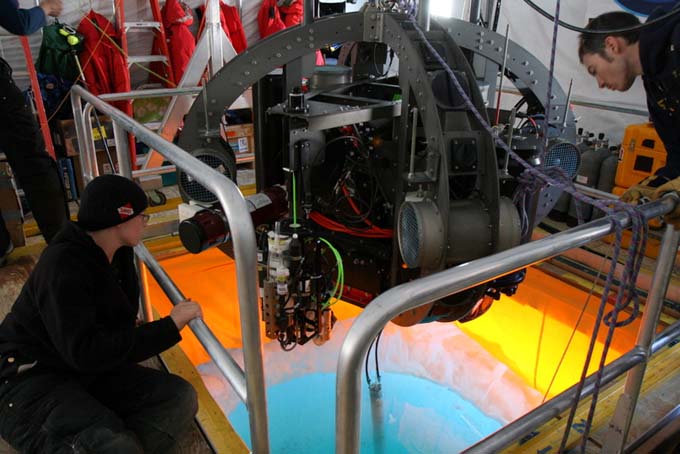

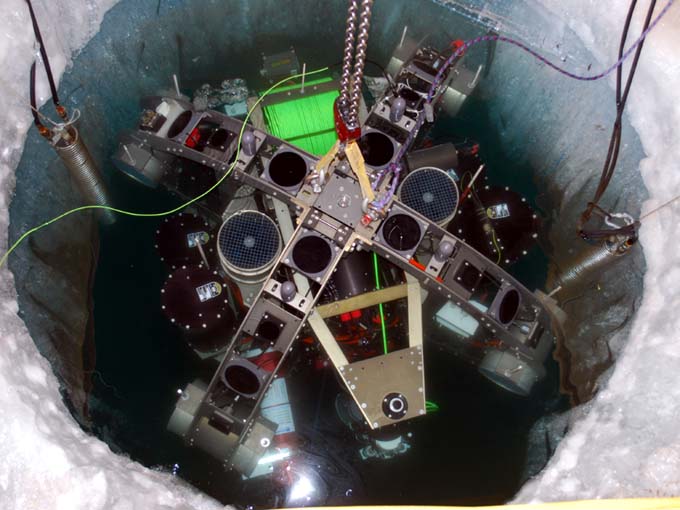

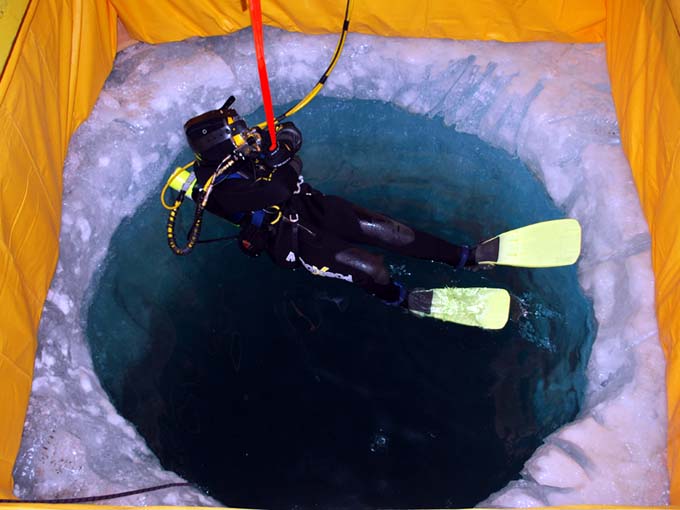

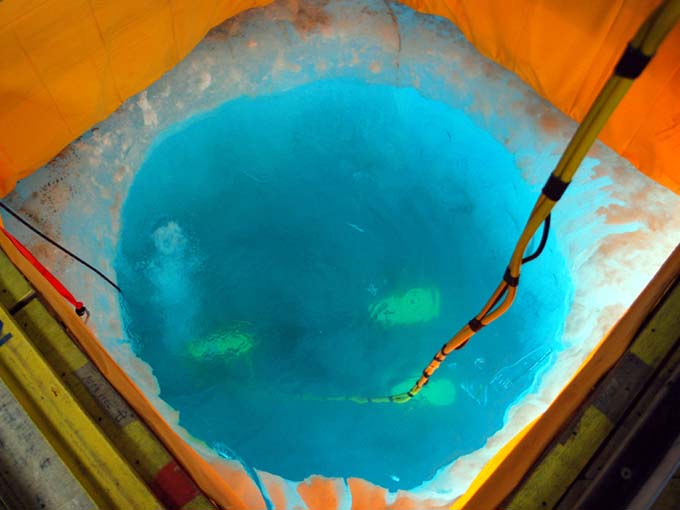

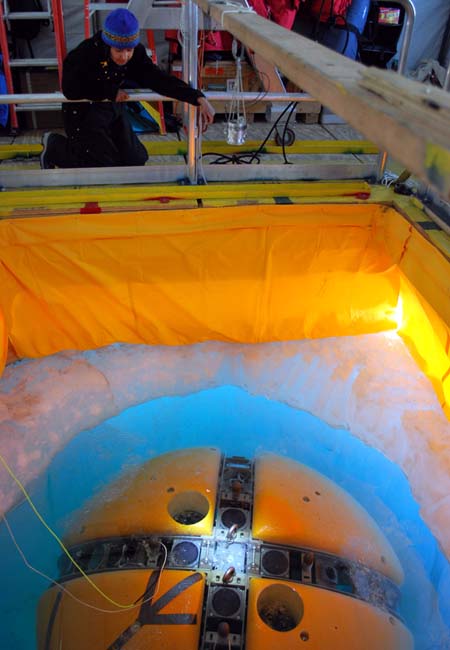

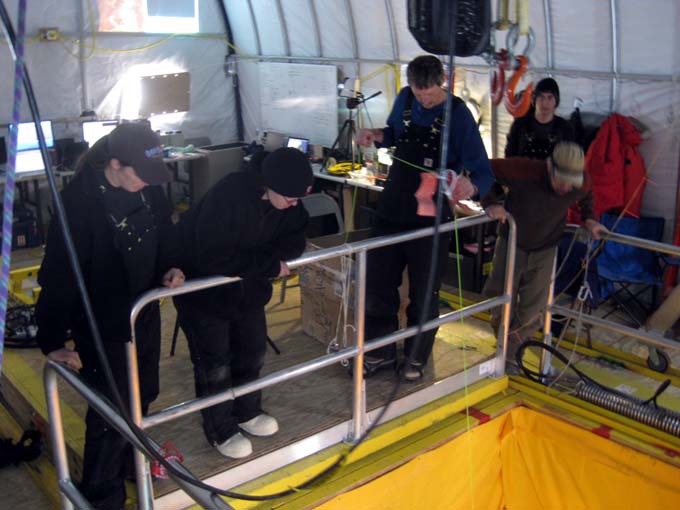

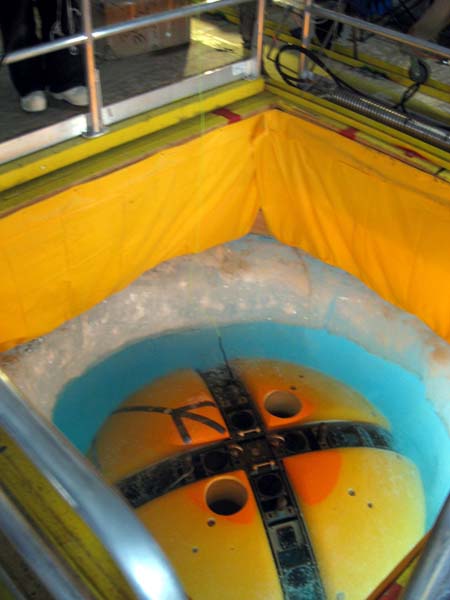

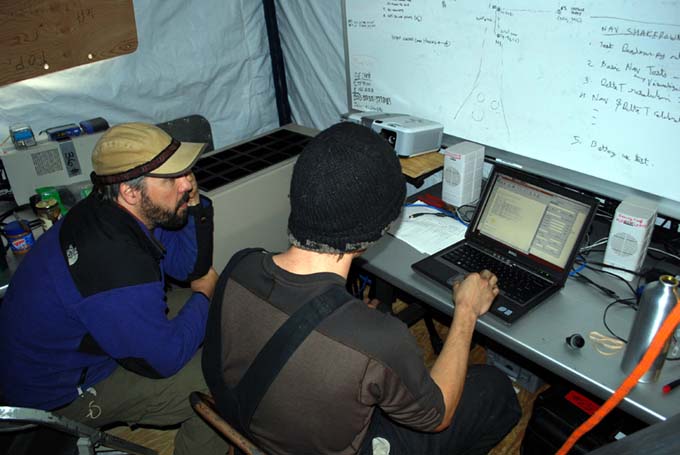

After a quick lunch we walked out to the 8 diameter ice hole that Maciej and Annika melted for us last week. For a quarter mile radius around the hole, the ice was strewn with sling loads of our gear lumber, tools, drums of fuel, and the wood panels that will make up the floor of our Bot House. The first task was to unload some of the tool boxes and lumber pallets. Once we had some tape measures in hand we were ready to start real work towards building the platform. Over the course of the afternoon we surveyed out the locations for the floor supports, stopping occasionally to duck low when additional helo deliveries arrived. By evening all of the floor supports were in place. The last sling load was set on the ice just as we all crawled into our tents for the night.

Bob, Bill and Bart decide where to place the floor supports around our ice hole. A couple inches of ice have refrozen on the water surface, making it safer for us to work around the hole.

Bob and Kristof unwrap a lumber sling load on the lake ice. The yellow wings are placed on the sling loads by the helo techs to stop the load from spinning as the helicopter flies through the air.

Reporting by Vickie Siegel